Authors: Yasser Kabbani MD and Abdul Rahman Tarabishy MD. West Virginia University Department of Neuroradiology

Editors: Matthew Tews, DO, MS, Department of Emergency Medicine and Hospitalist Services, Medical College of Georgia and Keith Baynes, MD, Department of Radiology, Medical College of Wisconsin

Learning Objectives

- Review basic anatomic landmarks in the brain

- Know the appropriate imaging work up for patients with head trauma/ stroke

- Recognize the different patterns of intracranial hemorrhage

- Recognize the various types of brain herniation

- Identifying signs of stroke on non-contrast CT

- Differentiate between mass vs. infection process on CT

Introduction

The key to reading a Computed Tomography (CT) scan of the brain is understanding the anatomy that you are looking at. Understanding the normal anatomy will allow the recognition of where structures should normally lay and therefore the ability to discern when abnormalities are present. Once the anatomy is known, a systematic review of the images should be performed so as not to miss any abnormal structures or potential disease processes. Repetition and review of many scans is the best way to learn the anatomy and to solidify a systematic way of reviewing images. However, it is challenging to accurately read and interpret a CT scan of the brain, so this chapter provides an introduction to systematically reviewing the scan and when to obtain in the Emergency Department.

A General Approach to the Evaluation of an Axial Imaging of the Head

A helpful mneumonic can be used when systematically reviewing the CT brain is Blood Can Be Very Bad:

| B | Blood | Blood |

| C | Can | Cisterns |

| B | Be | Brain |

| V | Very | Ventricles |

| B | Bad | Bone |

Blood

- Look for any evidence of bleeding: epidural, subdural, intraparenchymal, intraventricular, and subarachnoid

- Hyperdense (bright): Acute blood

- Isodense (similar to brain tissue): Subacute (at approximately 1 week)

- Hypodense (darker than brain tissue): Subacute to chronic (at approximately 2 weeks)

Cisterns

- Look for blood in the cisterns and to see if they are open

- Circummesencephalic (ambient)

- Suprasellar

- Quadrigeminal

- Sylvian

Brain

- Look comparatively at both hemispheres of the brain

- Check the grey-white differentiation to detect early signs of stroke. Compare both sides

- Evaluate the symmetry of the brain

- Make sure there is no midline shift which indicates an intracerebral mass, edema, or a herniation.

- Examine the brain parenchyma looking for anatomical distortion or altered attenuation indicative of a mass, bleed, or vascular malformation

Ventricles

- Examine third, forth, and lateral ventricles for dilation, compression, shift, and bleeding

- Compare the ventricle size to the patient’s age an look for discordance

Young Patient Ventricles

Elderly Patient Ventricles

Bone

- Examine the bone window looking for fractures, and evaluate the sinuses for fluid or soft tissues accumulation

- Fluid in the sinus may be a clue to a facial injury. Please note that if a facial injury is suspected, a CT of the head is not adequate. A dedicated facial CT is necessary to evaluate the entirety of the facial bones.

Bone Windows on CT

Additional Areas to Examine

- Major venous sinuses to detect hypo density which is indicative of thrombosis

- Venous thrombosis is a difficult diagnosis to make

- Look for a non-arterial distribution of ischemic change

- High clinical suspicion helps make diagnosis (risk factors)

- Venous thrombosis is a difficult diagnosis to make

- Soft tissues and skin through the parenchymal window looking for lesions or hematomas

- Soft tissue injuries noted on the scan should initiate a detailed evaluation of the subjacent structures.

- Check the orbits

- Look at every image from base to vertex of skull

- Review sagittal and coronal reformats if available

- Small extra axial hemorrhages, particularly along the tentorium are better seen on the reformatted images

How to Determine the Appropriate Brain Imaging Study in the Emergency Department

- Non contrast head CT should be used in emergent settings. It has an excellent sensitivity for Intracranial hemorrhage and is widely available, cost effective, and shorter imaging time in comparison with MRI.

- Do not use contrast because it can potentially obscure small hemorrhages.

- Contrast can be utilized in a follow up exam if necessary

- Typically CT angiography to evaluate vasculature (aneurysm)

- MRI is the most accurate imaging test. It’s the initial test in the outpatient setting (seizure or a history of remote trauma). MRI has better soft tissue contrast resolution when compared with CT and also has increased sensitivity for subacute and chronic blood products.

- The length of time to acquire the study limits efficacy in emergent situations although with improvement in technology and development of abbreviated ER department protocols, this may begin to change.

Cases

Case 1

A 28 year old male is flown in by helicopter to your emergency department after falling 20 feet at a construction site. Bystanders report he had LOC. When EMS got there, he was awake but moaning. Shortly after he became combative so was intubated for airway protection. On physical exam you note his pupils to be sluggish but symmetric. He has a large scalp contusion and laceration to the L parietal area. As part of his work up, a head CT is ordered. What findings do you look for in the CT?

Suspected Diagnosis: Epidural hematoma

What to look for:

- Blood – look for hemorrhage – subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, cerebral contusion

- Cisterns – look to see if they are open or compressed

- Brain – look for midline shift

- Ventricles – look for compression or blood in them

- Bone – look for skull fractures in the area of the blood on the bone window

- Classic epidural hemorrhage (EDH) has biconvex/lenticular shape

- The source of bleeding is often the middle meningeal artery

- Epidurals do not cross sutures, because this is where the Dura attaches to the skull. Thus epidurals result in medial bowing of the Dura, with Dura remaining fixed at its attachment sites

- Classic subdural hemorrhage (SDH) is Semilunar , or Crescent-shaped

- The source of bleeding is the bridging veins that cross the subdural space which is located between the arachnoids mater and the Dura mater

- It’s found along the cerebral convexity and bilateral tentorium cerebelli

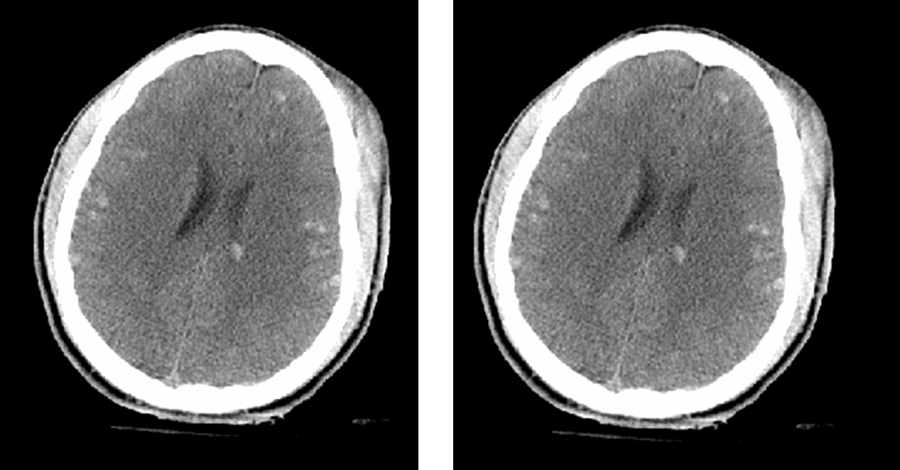

Diffuse Axonal Injury on CT Brain

Diffuse Axonal Injury on MRI

- Diffuse Axonal Injury (DAI) is a devastating type of head trauma results from acceleration-deceleration injuries.

- Often coexists wtih other traumatic findings

- On CT there may be numerous minute punctuate hemorrhages at the grey-white interference

- On CT, the severity of DAI can be underestimated, particularly on initial imaging.

- MRI is more sensitive.

- Consider DAI in the right clinical setting or when the clinical situation is much more than the imaging suggests.

Case 2

A 76 year old female was having breakfast with her family when she suddenly grabbed her head and slumped over. Family lowered her to the ground and she was in and out of consciousness and had vomiting. There was no seizure activity. Upon arrival to the ED, she has no verbal response, is not obeying commands and has snoring respirations. HR is 45 and her BP is 195/95. ECG shows sinus bradycardia. L pupil is poorly reactive. She has acute altered mental status, vomiting, unequal pupils and signs of Cushing’s reflex (low HR, elevated BP and irregular respirations). A brain CT is ordered.

Suspected Diagnosis: Subarachnoid hemorrhage

What to look for:

- Blood – look for hemorrhage – subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, cerebral contusion

- Cisterns – look to see if they are open or compressed

- Brain – look for midline shift

- Ventricles – look for compression or blood in them

- Bone – look for skull fractures in the area of the blood on the bone window

- Subarachnoid Hemorrhage (SAH) appears as hyperdensity in the Sulci, cisterns or ventricles.

- Subarachnoid space is located between the Pia mater and the Arachnoid mater

- In the absence of history of head trauma, it’s usually resulted from aneurysms, arteriovenous malformation (AVM), Cocaine, vasculopathy, or coagulopathy

- Aneurysms of the anterior communicating artery are the most common Circle of Willis aneurysm, and the most common cause of SAH

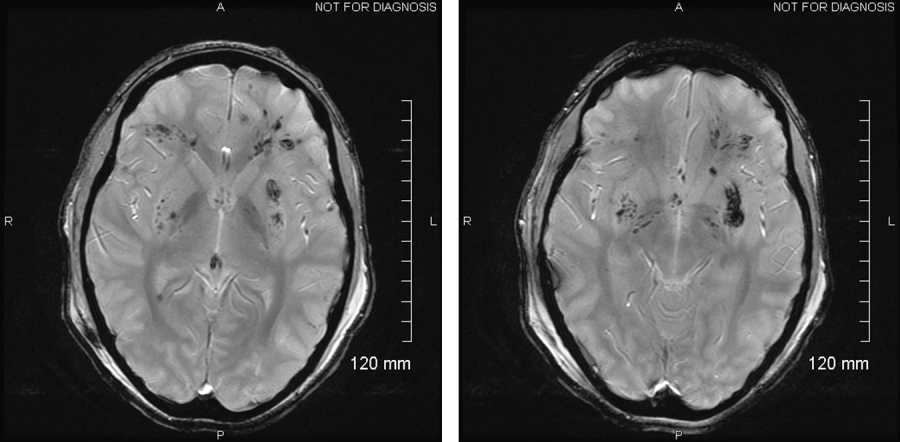

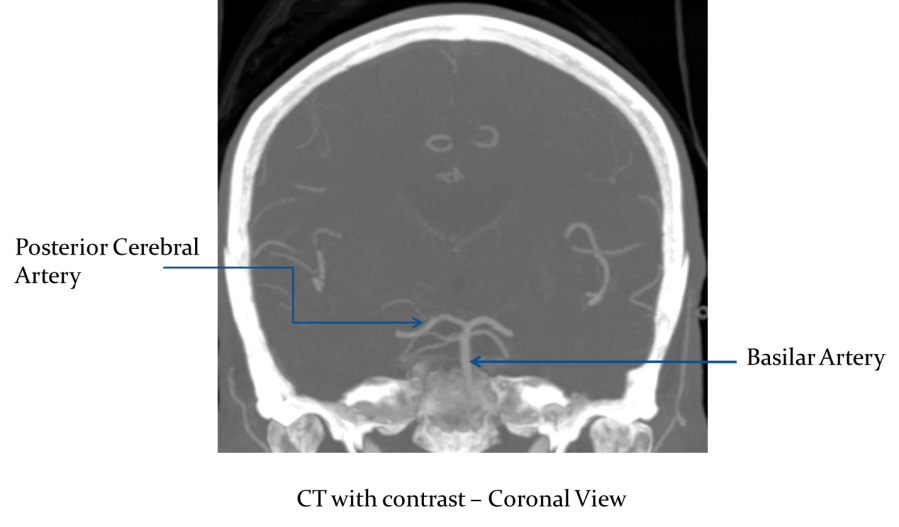

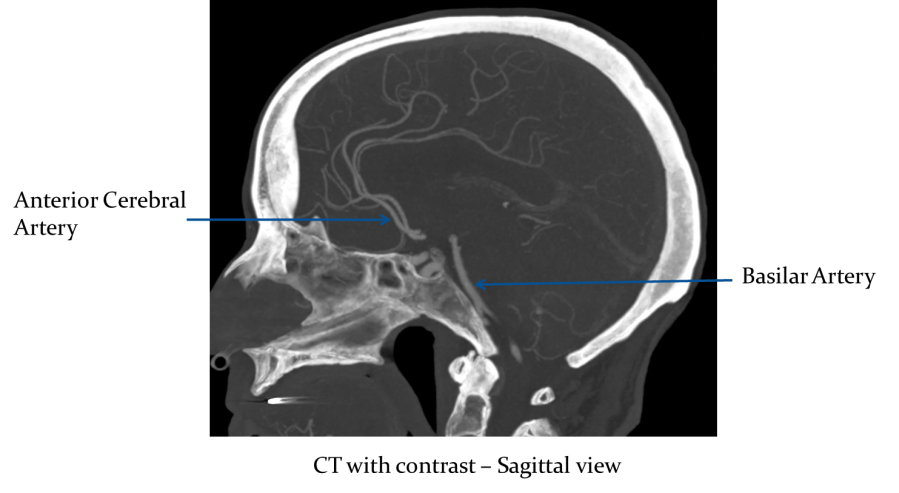

- Below are the vessels commonly associated with the Circle of Willis:

Circle of Willis Aneurysm (Anterior Cerebral Artery) = Yellow Arrow

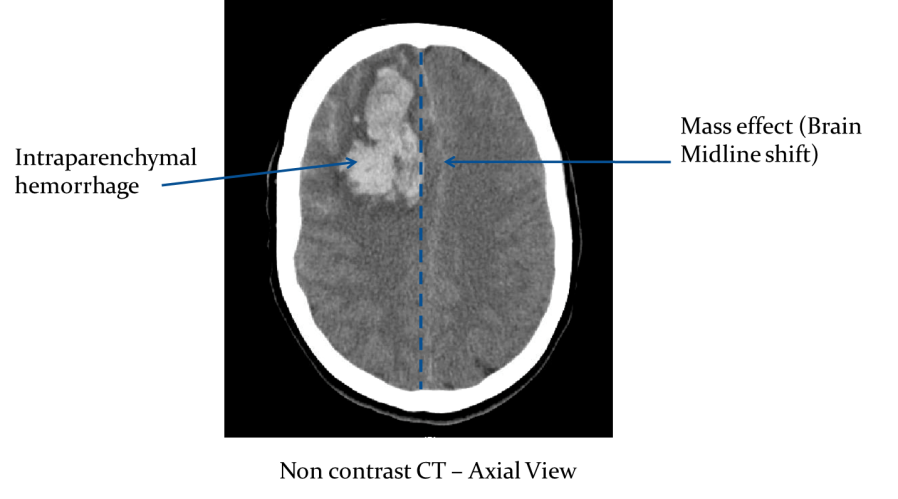

Alternate Diagnosis: Intraparenchymal Hemorrhage

- Intraparenchymal hemorrhage

- Non traumatic causes include: Hypertensive Hemorrhage, aneurysm, AVM, drug induced, and Tumor necrosis

- Hypertensive Hemorrhage typical places:

- Basal Ganglia (80%)

- Pontine (10%)

- Cerebellar Hemispheres (10%)

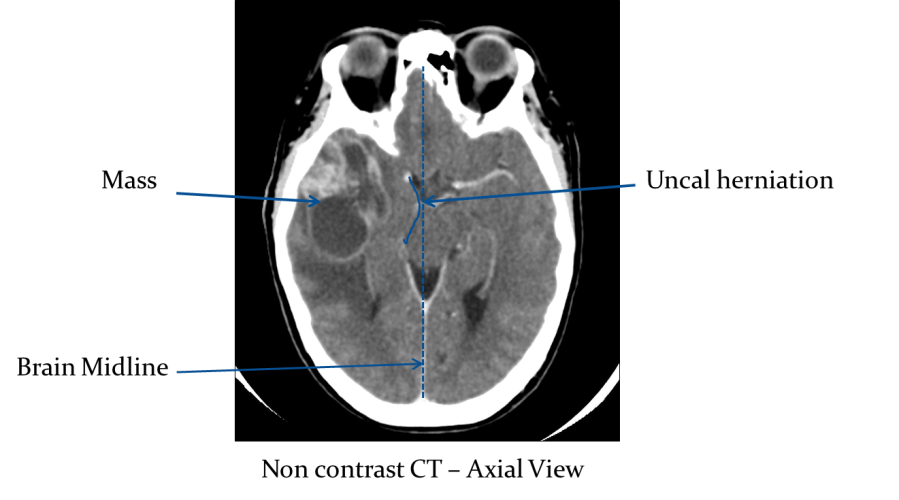

Potential Complication: Brain Herniation

A potential complication of swelling or bleeding in the intracranial space is herniation. There are several potential areas where herniation may occur.

- Brain herniation occurs when the intracranial pressure (ICP) increases to the degree that the brain in the affected area attempts to extend into a separate compartment

- It’s life threatening condition and classified as follow:

Supratentorial herniation

- Uncal

- Descending Transtentorial

- Subfalcine

- Extracranial

Infratentorial herniation

- Ascending Transtentorial

- Tonsillar

- Uncal herniation is when the medial portion of the anterior temporal lobe is shifted into the suprasellar cistern. It is a subset of descending transtenorial herniation, which is when the cerebral hemisphere crosses the tentorium at the level of the incisura. It can result in Infarct in the PCA distribution

- Subfalcine herniation is when the brain is shifted underneath the falx. It is the same thing as midline shift. It can result in hydrocephalus resulting from ventricular compression; infarct in the ACA distribution due to ACA compression

- Tonsillar herniation occurs when cerebellar tonsils move downward through the foramen magnum possibly causing compression of the lower brainstem and upper cervical spinal cord

Case 3

59 year old male was at work when he developed sudden onset of slurred speech and right sided weakness. Upon ED arrival his fingerstick glucose was 112 and his BP was 205/100. On neuro exam his right upper and lower extremities are flaccid and he is aphasic. He will obey commands and has normal strength to the L arm and leg.

Suspected Diagnosis: Cerebral Vascular Accident (CVA or stroke)

What to look for:

- Blood – look for hemorrhage – subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, cerebral contusion

- Cisterns – look to see if they are open or compressed

- Brain – look for midline shift

- Ventricles – look for compression or blood in them

- Bone – look for skull fractures in the area of the blood on the bone window

In this case, there are no abnormalities on the BCBVB mnemonic. However, there are other abnormalities to look for in the setting of suspected CVA.

- Exclude intracranial hemorrhage, which would preclude thrombolysis

- Look for early signs of stroke:

- Hyperdense Artery sign (the occlusion is visible)

- Loss of the insular ribbon sign (loss of definition of the gray-white interface in the lateral margin of the insular cortex)

- Exclude other intracranial pathologies that may mimic a stroke, such as tumor

The following images demonstrate the appearance of a stroke in the middle cerebral artery distribution of the brain, which correlates to the deficits described in this patient

A suggested approach to the imaging work up of the suspected stroke patient:

- Non contrast head CT to evaluate for hemorrhage/mass

- CT angiography is used to confirm the visualization of the occlusion.

- MRI is the most accurate test to detect ischemia. However, it is more time consuming and can delay the initiation of thrombolytic treatment.

- MRI Diffuse Weighted Imaging (DWI) sequence has a major role in the early identification of the acute infarction

Pearls and Pitfalls

- A useful pneumonic to remember when interpreting a head CT is “Blood Can Be Very Bad” (bleeding, cerebral cisterns, bones, ventricles, and brain.)

- Acute subdural blood will appear white (hyperdense) on CT, but as it evolves its density progressively decreases.

- Subacute to chronic subdural blood may become isodense to the adjacent brain and be difficult to detect.

- Multiple episodes of bleeding into the same collection can result in more than one density of blood products

- Head CT is not 100% sensitive in ruling out subarachnoid hemorrhage. It is most sensitive in the first 6 hours after symptom onset. After that, it becomes progressively less sensitive. If the clinician has a high index of suspicion for this diagnosis, a lumbar puncture is indicated.

- Choroid calcifications appear bright white on head CT and may be mistaken for blood. It is useful to know the appearance and location typical for choroid plexus so this normal anatomy will not be misinterpreted.

- It is helpful to compare your current CT scan to any prior imaging available.

- IV contrast is useful for evaluating brain masses and abscesses.

- CT scans can be viewed on different windows. A skull fracture is best seen in the bone windows and may be missed on the brain windows.

- Compare the 2 sides of the brain to look for mass effect.

- CT findings of stroke may be not be visible on an unenhanced head CT in the first few hours after symptom onset. The first visible sign is loss of grey white matter differentiation.

References

- Perron AD, Huff JS, Ullrich CG, Heafner MD, Kline JA. A multicenter study to improve Emregency Medicine residents’ recognition of intracranial emergencies on computed tomography. Ann Emerg Med. 1998 Nov; 32(5):554-62

- Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2010 Dec;33(4):821-54. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2010.08.006.

- http://www.slideshare.net/kunalmahajan50/basics-of-ct-head-by-dr-kunal-mahajan

- Head computed tomography interpretation in trauma: a primer. Broder JS

- Interpretation of Emergency Head CT: A Practical Handbook 1st Edition, Erskine J. Holmes Cambridge University Press; 1 edition (June 9, 2008)